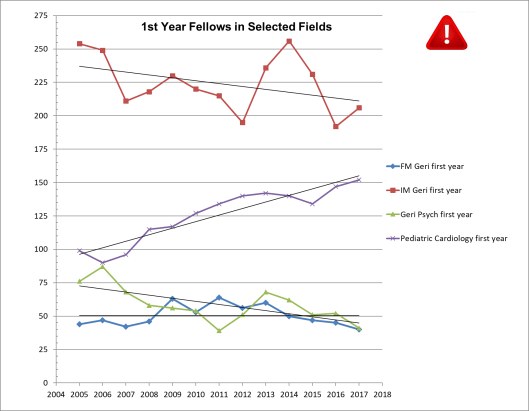

Once again it is time for my annual update on the number of physicians in geriatrics fellowship programs[1]. While this number might seem to be the eldercare workforce equivalent of looking for your wallet under the street light rather than out in the dark where you lost it, as I’ve argued in past years, the trend over time is actually a good measure of interest in the field of aging and reasonably reflective of the fortunes of other geriatric specializations in healthcare (e.g., nursing, social work, etc.), as well as being a very cheap and easy measure[2].

And, as usual, there just isn’t much good news to report. As the 13 years of data show, the overall trend is downward or flat in all three specializations in geriatrics: internal medicine, family medicine, and psychiatry. This year’s tiny uptick in internal medicine-based geriatric fellows is more than offset by the decline in family medicine and psychiatry. The fill rate for positions is still just around 50% meaning that there are as many funded slots empty as there are filled and the rates of “foreign medical graduates” in fellowship slots remains astoundingly high, indicating that US medical school training is still not setting physicians onto the path into the discipline. (And Pediatric Cardiology, our comparison group, seems to be back on its growth track. . .)

Somehow, I am reminded of an interaction I had about 10 years ago with an esteemed leader of one of the most prestigious academic medical centers in the country. This leader visited me at my prior employer, chaperoned by his geriatrics division chief, who was also a long-time grantee of the foundation with grant support to produce future geriatrics faculty. After an oddly lackadaisical pitch for funds for some purpose I don’t really recall, this esteemed eminence decided to offer some free advice – “You know what geriatrics needs? A big research award to attract the best and brightest faculty and draw attention to the field, that’s what will make the discipline strong.” As he said this I could see his geriatrics person, blanch as the foundation had been part of a funding consortium for just such an award since the mid ‘90s (The Paul B. Beeson Award[3]) and their esteemed institution was the nation’s biggest winner of such junior faculty support.

So, I allowed myself to gently snark back, that perhaps this theory of influence on the career choices of physicians was not complete. And I mentioned the then hot idea of medical students learning to “follow the ROAD” – into residencies in Radiology, Orthopedics, Anesthesiology, and Dermatology. These disciplines are famously lucrative and offer excellent quality of life, with scheduled, predictable work and few distraught people calling late at night. But I was quite surprised that he effortlessly snarked right back that research in these disciplines had created interventions and services that people found valuable, thus earning the pay that they received. Given that this is not exactly the way that reimbursement for physician specialty services is determined, I didn’t agree, and our mutual friend rapidly changed the subject.

But I am still struck that this department chair didn’t really disagree that pay was correlated with career choice, but only amended that pay was determined by something near and dear to his eminent heart – the research base that creates powerful and impactful interventions.[4] Does geriatrics have powerful and effective interventions? This is a question I’ve asked myself many times. Is it true that more training in elder care makes health professionals more proficient and able to help their patients get better outcomes? From time to time I’ve doubted, but I think the evidence is quite clear to the open mind. Geriatrically expert care is better. Through large scale research (e.g., the ACOVE program[5]) and my personal experiences, I’ve learned that older people frequently get care that fails them. They can be over treated in ways reduce function and make them sicker. They can be undertreated in ways that ignore solvable problems. And they can be mistreated in ways that leave them frightened and suffering.

Unfortunately, this perception is not shared by the public nor by generalist physicians. The public doesn’t want to be old and doesn’t want to admit that their health issues (and treatments) are a problem until it is too late. The health professions don’t want to admit the sins against common sense that they make all too often in care of older adults – too many drugs, too little assessment of symptoms written off to “aging” and too much testing and treatment that isn’t going to matter anyway.

So, let’s turn it around – rather than moan about how people aren’t drawn into geriatrics because Medicare’s reimbursement is low (making the income low) – let’s look at who is serving complex older adults in non-fee-for-service roles and if geriatricians are taking/getting these jobs that would seem to be the best use of their skills.

So, let’s turn it around – rather than moan about how people aren’t drawn into geriatrics because Medicare’s reimbursement is low (making the income low) – let’s look at who is serving complex older adults in non-fee-for-service roles and if geriatricians are taking/getting these jobs that would seem to be the best use of their skills.

As we all know by now 5% of the population drives 50% of healthcare spending. The poster child for this spend is the homeless man who uses the ED in lieu of housing, food, and when it is very cold. However, half of those 5% of people are over 65 and have much quieter and less public problems yet still wind up in the ED and hospital enough to make it into the group of elite “high utilizers.” And with the shift from “volume to value” there is a case for effective management and prevention for this population.

And this is a “hot” part of healthcare. The knowledge of the concentration of costs in a small population (many of whom are older Medicare beneficiaries) and capitation/sub-capitation has created a role for specialist provider organizations such as Iora and CareMore, which may be part of Medicare Advantage plans or partner with one. These organizations design their processes and staffing for complex older adult patients with substantial health problems and social needs. Similarly, working with fee-for-service beneficiaries, Medicare’s Accountable Care Organizations (AKA Medicare Shared Savings Programs) seek to hit quality and outcome targets while simultaneously reducing total healthcare costs. While these organizations are defined by the population attributed to a network of primary care physicians, they are required to have medical directors to work within the system to design processes, educate their colleagues, and improve care.

These specialized delivery roles and specialized health system roles are something I’ve long wished would develop. They create the hope that expertise in geriatrics could be profitable rather than a financial looser. They get geriatrics out of the trap created by Medicare’s set prices for cognitive services. Moreover, if geriatric expertise is valuable, it should be “bid up” in price given the limited labor supply, perhaps eventually drawing more physicians into the field (and fellowships).

So, are geriatricians being employed in these specialized care systems? First, I looked at the executive leadership of Iora and CareMore including the corporate level medical directors. None of the leaders in these organizations have done geriatrics fellowships. In the case of CareMore that was the limit of the information I could find, while clinical sites are listed (in California, Nevada, and Arizona) the drill down to physician specialty of those staffing sites is not easily available. In the case of Iora, the corporate website does link down to teams at sites around the country. I looked at the specialty of 10 physicians working at 6 Iora sites (including the original Dartmouth site, but not sites specializing in other population segments e.g., women’s health). Of those 10 physicians, 1 was a geriatrician. (It was Marty Levine, MD – the first fellowship trained geriatrician hired by Group Health Cooperative back in 2001 with a boost from JAHF. Hey Marty, are you still with Iora?)

With this disappointing result in hand, I reviewed the leadership of the 15 Medicare ACOs in the New York City, Westchester, and Long Island region. In addition to the usual urban advantage in physician workforce, one of the special advantages of health systems in this region is the large number of geriatric fellowship programs and the (relatively) large number of geriatricians trained here. If I ran a health system and my business strategy was to earn a share of the savings on reduced spending on my Medicare beneficiaries, I think I would very much want someone with a strong foundation in care coordination, multidisciplinary care, and aging. Unfortunately, looking at the leadership of the 15 ACOs listed on the very helpful CMS website, I see no geriatricians as medical directors. There are five general internists, two anesthesiologists, two gastroenterologists, a family physician, an emergency physician, a spattering of other IM specialties, and a pediatrician. No sign of a bidding war for geriatricians.

Just to be sure that I wasn’t having a spelling problem or that Google was broken or something, I looked up the leadership of PACE programs around the country. I got bored after looking at 6 pace programs, 4 of which had geriatricians serving as medical directors (along with 1 pediatrician!). A small sample, but perfectly adequate to prove that I can find geriatricians when they are there. Unfortunately, while PACE programs are a good use of geriatricians, PACE nationally has failed to grow and cares for a very small number of albeit very frail older adults (fewer than 60,000).

I wonder what a wider analysis might find? What about Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs) which have nearly 2 million older adult enrollees. What about Independence at Home programs? Medical Directors of integrated “Duals” plans? Leadership at CMS? (Not to be mean, but both Don Berwick [former CMS head] and Patrick Conway [former CMS Chief Medical Officer, among other hats] were pediatricians.) Are there other factors at work? Is the ethos of the field such that geriatricians just don’t venture out of academic institutions? Does the one-year geriatrics fellowship not provide the cool tools for modern “population health?” This seems like an issue that warrants serious analysis to understand and correct. Geriatricians don’t seem to be employed where their clinical skills would seem to be most valuable (outside of PACE programs) nor do geriatricians seem to be employed in systems leadership jobs where they could have an indirect ,but vital, impact on care.

What’s going on here?

[1] Geriatrics is a physician specialty in internal and family medicine as well as in psychiatry. Specializing in geriatrics in one of these fields gives a physician a year of focused clinical training across a range of settings, mentored by senior physicians in the discipline.

[2] The numbers come from the annual “education” report in JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and is a very high-quality review of the numbers of physicians in different training programs, both at the residency level and the specialty (fellowship) level of training. See https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2666480

[3] The Paul B. Beeson Award is just now winding down as a partnership supplementing more usual career development awards from the National Institute on Aging. https://www.afar.org/research/funding/beeson/

[4] Cynically you could ask if the interventions in these fields were really powerful and impactful on health or that their attraction was really a form of “gizmo idolatry” from which Americans professional and lay seem to suffer – equating big machines and flashing lights to the quality of care.

[5]See the paper archive at: https://www.rand.org/health/projects/acove.html

I came to this realization when I recently read an

I came to this realization when I recently read an

If the effort that was used to collect ~30% response rate from the 1,164 people had been used to collect responses from a planned, representative sample of 300 people, the estimates would be impacted by sampling error, but not the same uninterpretable bias due to respondent self-selection. With 300 respondents the margin of error would be +/- 4.5% for percentage estimates around 80%. Margin of error at the 95% confidence level for percentages is calculated using the formula * +/- 1.96. So if we were to find that 80% of the respondents were still in the field of geriatrics our sample error would be and we would have 95% confidence that the true proportion was between 75.5% and 84.5%. In fact, even if we had a sample of only 100 the margin of error at the 95% confidence level would still be less than +/-1 10%. (+/- 7.8%, to be precise)[v],[vi].

If the effort that was used to collect ~30% response rate from the 1,164 people had been used to collect responses from a planned, representative sample of 300 people, the estimates would be impacted by sampling error, but not the same uninterpretable bias due to respondent self-selection. With 300 respondents the margin of error would be +/- 4.5% for percentage estimates around 80%. Margin of error at the 95% confidence level for percentages is calculated using the formula * +/- 1.96. So if we were to find that 80% of the respondents were still in the field of geriatrics our sample error would be and we would have 95% confidence that the true proportion was between 75.5% and 84.5%. In fact, even if we had a sample of only 100 the margin of error at the 95% confidence level would still be less than +/-1 10%. (+/- 7.8%, to be precise)[v],[vi]. that because the response rate was low, that the program couldn’t have been good, even for follow-ups done many years later.) Sampling is a mildly technical concept that adds a layer of mystery that “survey” doesn’t have. I also suspect that accepting the certainty of sampling error is an upfront loss, and there is a natural human tendency to try to avoid such a certain loss, even the logically expected outcome of an uncertain option is even worse. We all tend to hope that “this time it will be different” and make the perfect the enemy of the good enough.

that because the response rate was low, that the program couldn’t have been good, even for follow-ups done many years later.) Sampling is a mildly technical concept that adds a layer of mystery that “survey” doesn’t have. I also suspect that accepting the certainty of sampling error is an upfront loss, and there is a natural human tendency to try to avoid such a certain loss, even the logically expected outcome of an uncertain option is even worse. We all tend to hope that “this time it will be different” and make the perfect the enemy of the good enough.